As Remembrance Sunday approaches we thought a few stories of men (and it was predominantly men) who served, often making the ultimate sacrifice, in either of the World Wars, and who came from, or had strong connections with, the Black Country, would be timely. But where to start?

There are over 1500 graves cared for by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission across the Black Country, and these are the graves of soldiers sailors and airmen who died in the UK. Until the Falklands War in 1982, it was British Government policy not to repatriate the bodies of fallen warriors, in line with the 1918 report of the Imperial War Graves Commission (which itself emerged from the 1915 establishment by the British Expeditionary Force of a Graves Registration Committee, a voluntary group acting on the Western Front during the battles of 1914 and taken over by the army in March 1915). This report stated “. . . to allow removal (of bodies) by a few individuals (of necessity only those who could afford the cost) would be contrary to the principal of equality of treatment.” It further justified this policy as ” . . . those who fought and fell together, officers and men, lie together in their last resting place, facing the line they gave their lives to maintain” and that the dead *. . . would have preferred to lie with their comrades.” Not having a grave close to home on which family members could focus their grief was undoubtedly one of the reasons so many war memorials were erected in towns and villages, churches, factories and schools.

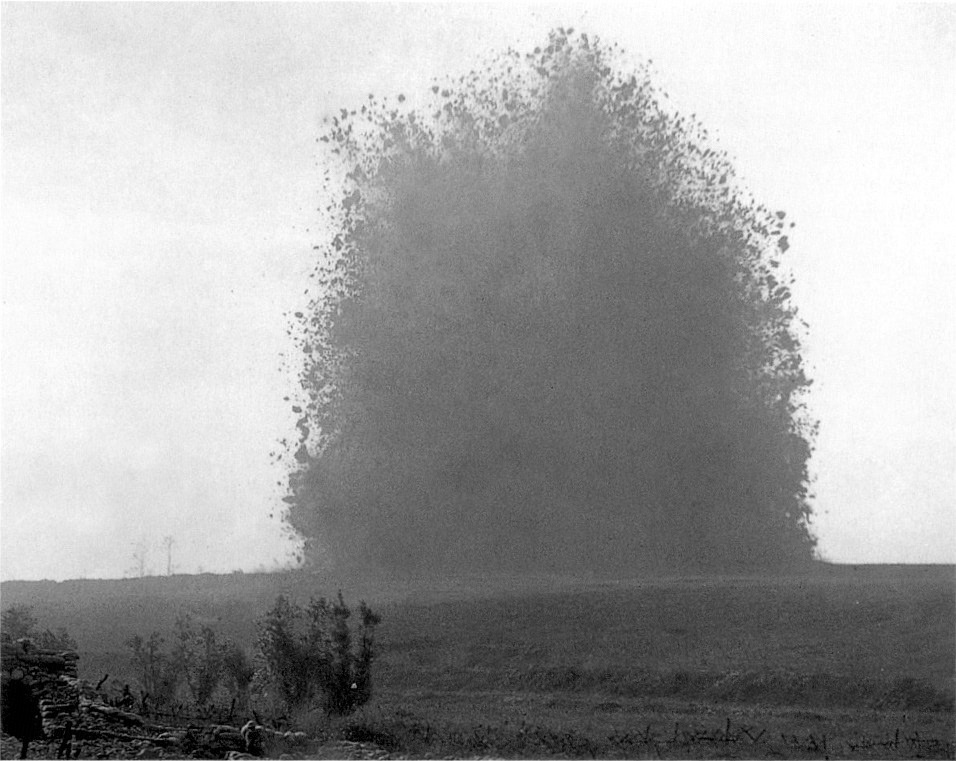

I said some weeks back that I wasn’t going to write about Black Country MPs for a while, but the Conservative MP for Wednesbury from 1910 to 1918, Jack Norton Griffiths does I think warrant a brief appearance in the run-up to our armistice and remembrance commemorations this weekend. This rather colourful character (he deserves an article to himself and will get one shortly) had an engineering background with significant experience of tunnelling – gold mines in South Africa, parts of the London underground and the sewage systems in Deptford Battersea and Manchester. So when the fighting on the Western Front turned into trench warfare both the German and French armies took to tunnelling under no-mans land and planting explosives under the enemy trenches.

On December 20th 1914 10 small mines were exploded under the trenches occupied by Gurkha and Highland Light Infantry soldiers of the recently arrived in France Sirhind Brigade, causing heavy casualties, with over 800 men killed. The British Army had been looking at how to develop its own tunnelling units since early December, and Norton Griffiths was given the job. He closed down one of his tunnelling contracts in Manchester and on 18th February 1915 the 18 men made redundant were recruited as Royal Engineer sappers. They were in France 4 days later having undergone almost no military training, so pressing was the need to take on the Germans in the developing underground war. By March 1915 there were eight tunnelling companies operational, each consisting of around 270 men, and by August another 12 had been formed.

Initially Norton Griffiths recruited ex miners from regular regiments, and from the Lancashire and Scottish coalfields as well as tin miners from Cornwall. In July 1915 he returned to England to resume his duties as Wednesbury’s MP, but carried on recruiting for the tunnelling companies, with many men from the Black Country collieries joining up for 6 pence per day, more than was paid a regular soldier.

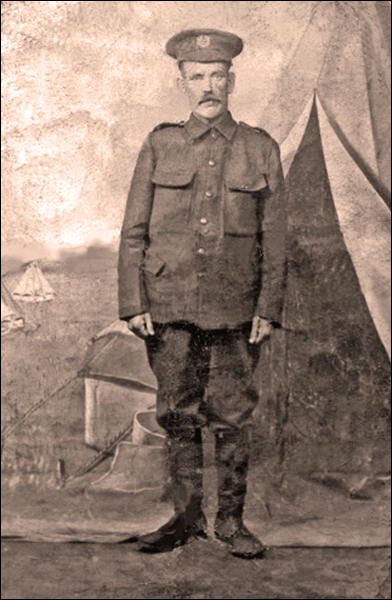

According to family legend, a small group of friends from Tipton, all employed as coal miners, decided after a drinking session one afternoon in their local pub to enlist, and marched down to the local recruiting office to sign up. In fact, the friends, including Ezekiel Parkes who lived in Princes End in Tipton and worked at Baggeridge Colliery in Sedgely, and John Lane also of Tipton travelled to London by train in August 1915 and enlisted in front of Norton Griffiths in his office in Westminster. Norton Griffiths had continued to personally encourage recruits to join the mining companies on his return to England from the front. Ezekiel was in France by 26th August, and John arrived on 7th September. In October they found themselves part of a 3 man team of the newly formed 179 Tunnelling Company Royal Engineers, and sent to Givenchy on the Somme.

Before long they were digging tunnels towards the German trenches through thick clay almost 75 feet underground, working a daily 6 hour shift which saw the tunnel advance little more than two feet (about 0.6m) per shift.

Tragedy struck on November 22st. Captain Henry Hance of the Royal Engineers, officer commanding the tunnel, wrote a comprehensive account of what happened in the early hours of November 22nd.

I have to report that the enemy blew a very heavy mine at 1.30am from a point in sub-Sector E3 about 50 yards North of point 120, killing, I regret to say, a Cpl. And 5 sappers of this Company, and, I am informed, 7 men of the 10th Essex Regt.

I was informed that our W shaft and galleries had been wrecked. I arrived at the spot shortly after 2am by which time the men at the top of the shaft had got out of the adit by the underground communication with X into Quemart, the adit entrance into W being closed. The man employed working the air bellows was buried, but was extricated practically unhurt. A canary was lowered down the shaft to test the ventilation and was pulled up after one minute dead. In a very short time the first of our two rescue men arrived with his apparatus, and, as soon as he had put it on, another canary was lowered and after a minute was pulled up, also dead.

One of the rescue men was lowered on a life line, but at the bottom of the shaft found two of the men, both quite dead.

The bodies of Ezekiel Parkes and John Lane were never recovered. In January 1916 the Tipton Herald reported:

DEATH OF A PRINCES END MINER – Official intimation has recently been received of the death of Sapper E Parkes of the 179th Company of the Royal Engineers. Parkes is one of the thousands of brave miners who on the outbreak of war volunteered their services on behalf of King and Country. He was killed in action on November the 21st at a place not stated. His widow, who is left with a large family, lives at No. 36 Victoria Street, Prince’s End.

If you don’t have any family members to remember on Remembrance day, why not spend a few moments remembering Ezekiel Parkes and John Lane, who died in a cold damp cramped tunnel far below the surface of the earth, where their remains lie still today. Their sacrifice shouldn’t be forgotten. We should remember them.

Leave a comment