One of the very first World War One war memorials is on the edge of the Black Country. It is a beautiful stained glass window from the workshops of William Morris and Co., designed under the supervision of the Morris and Co. Artistic Director, JH Dearle and installed in St Mary’s, Oldswinford, in December 1915. Dearle was better known as a textile designer than as a glass painter, so how much he actually contributed to the window is debatable.

The window shows the scene from Matthew’s gospel (chapter 14) where Jesus saves the disciples from a storm on the sea of Gallillee by walking across the water to their boat. The disciple Peter tried to do the same but sank!

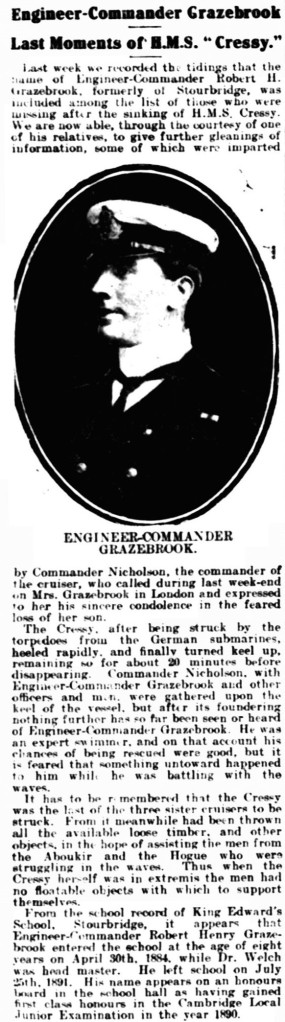

An appropriate memorial to a sailor who went down with his ship, the window was commissioned by his mother. It is just one of a number of memorials in St Mary’s, most of the others being made by West Midlands craftsmen and in particular members of the Bromsgrove Guild. Robert Grazebrook’s parents lived in London (although his father originally came from Pedmore) so it is understandable that his mother, who commissioned the window, would have been more familiar with the highly respected London based Morris and Co. rather than West Midlands makers.

Robert Grazebrook, who was born in Stourbridge, was a career naval officer born in 1876 who had joined the navy in 1891 aged 15 as a midshipman. He had served on the Royal Yacht VICTORIA AND ALBERT, then on HMS TARTAR and HMS SAPHO, and was appointed Engineer Commander (Chief Engineer with long service) on board HMS CRESSY earlier in 1914 .

Sunday 22nd September 1914 was a disastrous day for the Royal Navy: in the space of two hours three battle cruisers, HMS CRESSEY, HMS ABOUKIR and HMS HOGUE, had been sunk by a single German submarine, and it soon became apparent that of the 2,296 men on board them, only 837 had survived. Nearly 1500 sailors had been killed. There are many accounts of the engagement on line – If you want to read more then please follow this link. https://thedockyard.co.uk/the-collections/digital-exhibitions/three-cruisers/ .

But although the window commemorates Engineer Commander Robert Henry Grazebrook, he was not the only sailor to die on what proved to be a major disaster for the Royal Navy, a disaster which took the lives of a number of Black Country men, none of them with families wealthy enough to commission a memorial as grand as that at Oldswinford.

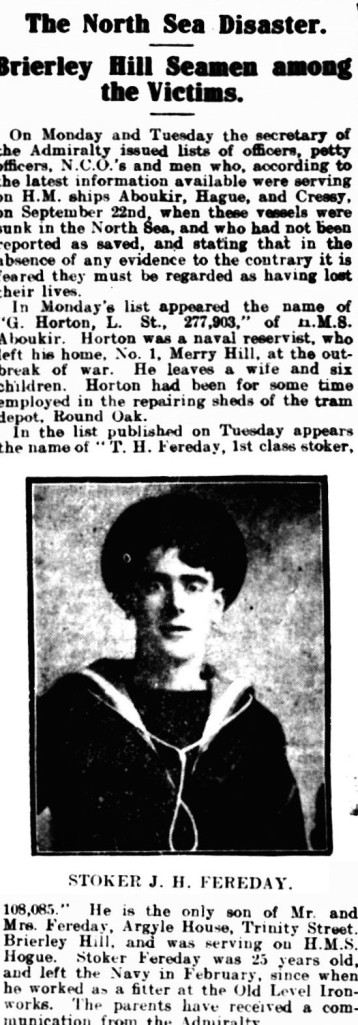

The Royal Navy recruited systematically in the Black Country in the late 19th and early 20th century. Not only was it a densely populated area, but also the Naval Recruiters believed that the Black Country, with is iron furnaces powered by coal and coke, produced a class of men well suited to the arduous task of stoking the boilers on board Royal Naval vessels, in the days when most warships were still powered by coal which had to be physically shovelled into the furnaces in temperatures that could exceed 40 degrees. And in the days following local and national newspapers began to reveal the names of the dead, the missing, and those that had survived, as news began to arrive back at the homes of husbands, fathers, brothers and sweethearts. Many of the survivors had been picked up by Dutch ships and landed in neutral Holland: it took a few days for accurate lists of these survivors to be compiled.

Many of the Black Country men on board were Royal Naval Reservists, either ex seamen who had left the Navy but committed to serve again in time of war, reservists who were serving in the merchant navy at the outbreak of the war. Many had been called up in late July 1914 (before war was declared – but that’s another story) and the lack of experience and training of so many of the crews on board the cruisers was seen as one reason for the disaster of 22nd September.

In addition to Robert Grazebrook, we have identified the following Black Country men who died on September 22nd and who were serving on one of the cruisers. This is almost certainly not a complete list but is made up from names on the Royal Navy memorials at Chatham and Portsmouth.

Jesse Webster, Petty Officer, from Wolverhampton,

John Warton, Stoker 1st class, of Greets Green West Bromwich,

EH Sillet, of Hallam St in West Bromwich,

GE Clemson Stoker 1st Class, born in Tipton,

Thomas Harold Fereday, Stoker 1st Class, from Brierley Hill (born in Tipton.)

Richard Beckett, Able Seaman, from Walsall

G Horton, Stoker, of Merry Hill

We have also tracked down one man from the Black Country who survived: Rev. C E P Ellis, chaplain on board HMS HOGUE, who in peacetime had been a curate at St Andrew’s church, Wolverhampton, and came from Great Barr.

I don’t think its possible to imagine what it must have been like for families waiting to hear news of their loved ones. But an account of an interview with Harold Fereday’s mother, in the Herald on 25th September, 3 days after the sinking, goes some way to illustrate the anguish worry and concern:

“His mother when interviewed said Harold is her only son,and the suspense was killing her. Just before our representative called, a telegram arrived which Mrs Fereday hoped was bringing news of her son, but instead it was from his young lady (Miss Mitchell) living in Lowestoft, who telegraphed begging for news of Harold: Harold’s last letter to her read: “I shall be glad when this is all over. Just fancy, five weeks and I have not had an all-nights sleep yet. It is all work here. I am pleased to say I am still alive and kicking”.

It is easy to be prompted to remember those who have such splendid memorials as Robert Glazebrook. But we should remember all the other casualties as well. Their, and their families sacrifices were every bit as devastating calamitous and heart-rending. And should never be forgotten.

Leave a comment